Symmetrical vs. Unsymmetrical Faults: A Practical Guide for Power Engineers

When something goes wrong in a power system, it happens fast. Currents surge, voltages dip or become unbalanced, and equipment can be damaged in milliseconds. Circuit breakers must operate instantly, and protection systems must respond with precision. To design, operate, or protect a power grid effectively, every electrical engineer must understand symmetrical and unsymmetrical faults. These concepts form the backbone of power system protection and reliability. Let’s break them down clearly and practically.

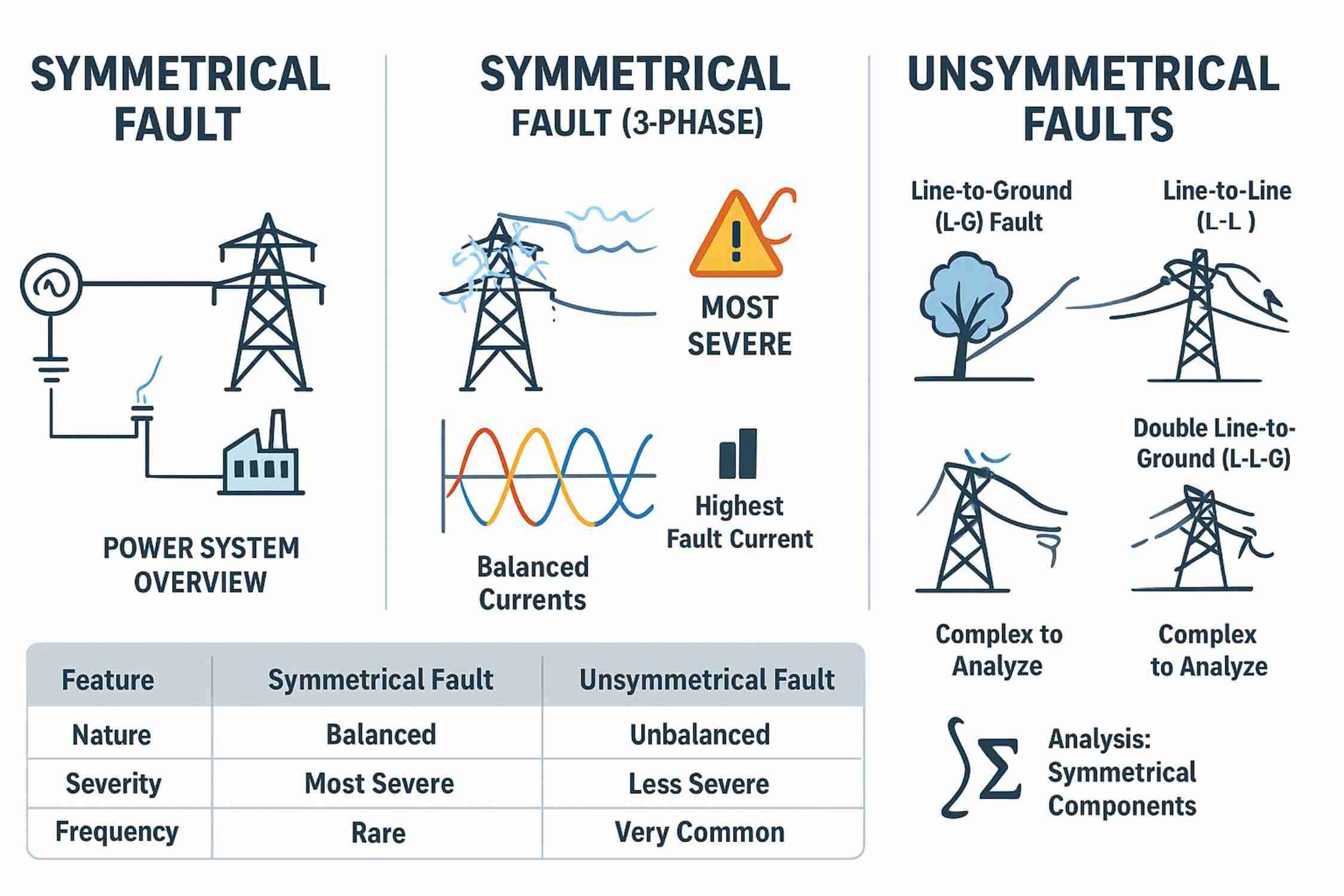

Symmetrical Fault (Three-Phase Fault)

A symmetrical fault occurs when all three phases are short-circuited together or all three phases are shorted equally to ground. Because each phase is affected equally, the system remains electrically balanced—even during the fault.

Although symmetrical faults are rare, they are extremely severe because they produce the maximum possible fault current in the system.

What Happens During a Symmetrical Fault?

- All three phases are shortened equally

- Currents remain balanced

- Voltages drop equally

- Fault current reaches its highest possible magnitude

Since the system remains balanced, analysis becomes simpler. Only the positive-sequence network is used in calculations.

Fault Current Formula

Ifault = Vph / Z1

Where:

- ( Vph ) = Phase voltage

- ( Z1 ) = Positive sequence impedance

Because only one sequence network is involved, calculations are straightforward—but the mechanical and thermal stress on equipment is enormous.

Protection Methods

To handle such high currents, protection must be extremely fast:

- Instantaneous overcurrent relays

- Distance relays

- High-speed circuit breakers

Even though these faults are uncommon, systems are designed to withstand them because of their destructive potential.

Unsymmetrical Fault (Unbalanced Fault)

An unsymmetrical fault affects one or two phases, leaving the system electrically unbalanced. These are the most common faults in real-world power systems.

Unlike symmetrical faults, unsymmetrical faults involve multiple sequence networks (positive, negative, and sometimes zero sequence), making analysis more complex.

Common Types of Unsymmetrical Faults

1) Single Line-to-Ground (L–G) Fault

This is the most frequent fault in power systems.

- One phase shorted to ground

- All three sequence networks are involved

- Produces unbalanced currents and voltages

Fault current:

Ia = 3Vph/ (Z1 + Z2 + Z0 + 3Zf)

Where:

- ( Z1 ) = Positive sequence impedance

- ( Z2 ) = Negative sequence impedance

- ( Z0 ) = Zero sequence impedance

- ( Zf ) = Fault impedance

2) Line-to-Line (L–L) Fault

- Two phases shortened together

- No ground involvement

- Zero-sequence current = 0

- Only positive and negative sequence networks are involved

These faults are less severe than three-phase faults but still produce significant mechanical stress.

3) Double Line-to-Ground (L–L–G) Fault

- Two phases are shortened together and connected to ground

- All three sequence networks are involved

- More complex analysis

This type combines characteristics of both L–L and L–G faults.

Protection for Unsymmetrical Faults

Because these faults create an imbalance, protection systems detect abnormal conditions such as:

- Ground relays

- Phase overcurrent relays

- Negative-sequence relays

- Earth fault protection systems

Negative-sequence protection is especially important because unbalanced currents cause overheating in rotating machines.

Why Fault Analysis Matters

Understanding faults is not just an academic exercise. It determines:

- Breaker interrupting ratings

- Relay settings

- Equipment sizing

- System stability

- Personnel safety

A poorly coordinated protection system can lead to cascading failures and widespread outages. On the other hand, a well-designed protection scheme isolates the fault quickly, keeping the rest of the grid stable and operational.

Final Thoughts

Faults are inevitable in power systems—caused by lightning, insulation failure, equipment breakdown, or human error. What defines a reliable system is not the absence of faults, but how effectively it detects and clears them. Mastering symmetrical and unsymmetrical fault analysis equips engineers to design safer, stronger, and more resilient power networks. In power engineering, fault knowledge isn’t optional—it’s foundational.