When Power Exists but Cannot Leave the Plant: The Evacuation Bottleneck.

The scene is a familiar and frustrating one in power engineering: the turbine is running smoothly, the generator is healthy, and megawatts of potential energy are available—yet nothing leaves the gate. This is one of the most critical and often misunderstood failures in the industry. It is a failure not of generation, but of evacuation.

Power generation and power delivery are fundamentally different concepts. A plant can be technically sound, with all its internal systems operating at peak efficiency, and still be electrically stranded. When power cannot leave the plant, the problem almost always sits outside the core process, residing at the interface between the plant and the grid.

The Bottleneck: Where Power Evacuation is Decided

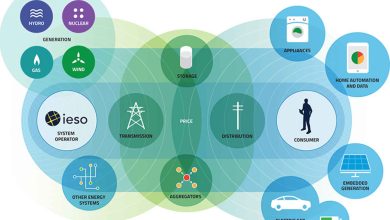

The power evacuation system determines a power plant’s ability to export its generated energy. This system is a complex chain of electrical infrastructure and operational agreements that collectively decide how much power can flow, not how much can be produced.

The primary components that form this bottleneck include:

| The maximum power that the Transmission System Operator (TSO) will accept based on system stability. | Role in Evacuation | Potential Bottleneck |

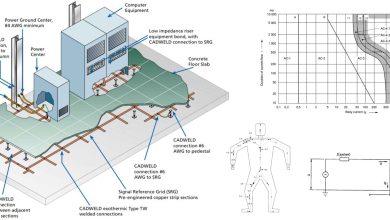

| Generator Step-Up (GSU) Transformer | Steps up the generator voltage to the transmission voltage level. | Failure, incorrect tap settings, or thermal limits can restrict power flow. |

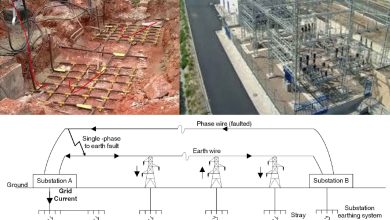

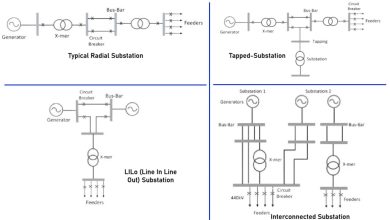

| Switchyard and Bus Configuration | Connects the GSU to the transmission lines and provides switching flexibility. | Poor design (e.g., single-bus configuration) can lead to a single fault stranding the entire unit. |

| Protection and Control Coordination | Relays that monitor the plant-grid interface and command circuit breakers. | Overly conservative settings can cause premature tripping during minor grid disturbances. |

| Transmission Lines and Right-of-Way | The physical path for power delivery. | Thermal limits, conductor sag, or lack of capacity dueating to transmission congestion . |

| Grid Acceptance Limits | The maximum power the Transmission System Operator (TSO) will accept based on system stability. | Tight operating margins or system instability can force the TSO to curtail plant output. |

Why This Happens (Even in “Good” Plants)

The core reason for this disconnect is that the grid is a dynamic, interconnected system, and the plant is just one node within it. Failures to evacuate power are rarely due to turbine problems; they are almost always a consequence of the grid’s inability to receive the power safely.

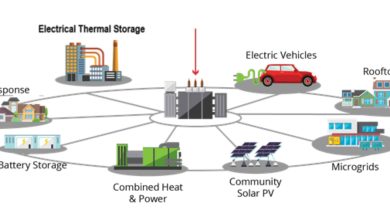

- Transmission Capacity Constraints: In many regions, the growth of generation capacity, particularly from renewables, has outpaced the development of new transmission infrastructure. This leads to grid bottlenecks, where the physical limits of the lines prevent full power flow.

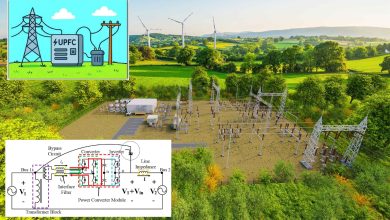

- Grid Instability and Weakness: A weak grid, characterized by high impedance or low short-circuit capacity, is highly susceptible to voltage and frequency fluctuations. The plant’s protection systems, designed to protect the generator, may trip the unit instantly when these grid faults are reflected back into the plant.

- Overly Conservative Protection Settings: Protection relays are often set with wide safety margins. While this ensures the generator’s safety, it can cause premature tripping during non-critical grid events, effectively stranding power.

- Load Rejection Scenarios: If a major transmission line trips, the plant experiences a sudden and massive loss of load. The plant must be designed to handle this load rejection without tripping or over-speeding, a scenario that often dictates the maximum power the plant is allowed to export.

The Quiet Reality Professionals Learn

The economic reality of power generation is stark: a megawatt not evacuated is a megawatt wasted. Availability without evacuation is merely theoretical capacity. The plant may be mechanically available 99% of the time, but if the grid allows power export only 80% of the time, the plant’s actual revenue-generating availability is significantly lower.

Grid interaction failures are rarely dramatic; they are persistent. They manifest as repeated curtailments, unexplained trips, and constant disputes over “underperformance.” This is why the design, testing, and coordination of the evacuation system—from the GSU to the TSO’s control room—deserve the same, if not greater, attention as the leading plant equipment.

Senior engineers understand this distinction. They do not ask only, “Is the unit available?” They ask the more critical question: “Can the grid safely receive what we generate?”

The key takeaway for every professional in the power sector is a simple hierarchy of value:

| Concept | Outcome |

| Generation | Creates Potential |

| Evacuation | Creates Value |

| The Grid | Decides What Is Real |

Power that cannot leave the plant does not exist in practice.

References

[1] Siemens. Energy crisis: Short of power, short of transmission capacity. Discusses the global challenge of grid bottlenecks and the need for increased transmission capacity.

[2] Invictus Sovereign. What Are Grid Bottlenecks? Impact on Clean Energy. Explains how infrastructure limitations prevent efficient energy transmission from source to consumption.