A Critical Analysis of Power Flow Limitations in Electrical Transmission Networks

Abstract

The reliable operation of bulk electrical power systems is fundamentally predicated on maintaining a continuous equilibrium between generation and load. This balance is facilitated by the physical flow of power across a network of transmission lines (T-lines), a process governed not by a single principle but by a complex interplay of three distinct and often conflicting physical limitations. This article delineates the tripartite constraints of thermal capacity, voltage regulation, and steady-state stability that collectively define the feasible operating envelope for AC transmission systems. Furthermore, it examines how modern power electronic-based solutions, including Flexible AC Transmission Systems (FACTS) and High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) technology, are mitigating these classical constraints, enabling systems to approach their theoretical limits with enhanced reliability.

1. Introduction: The Equilibrium Imperative

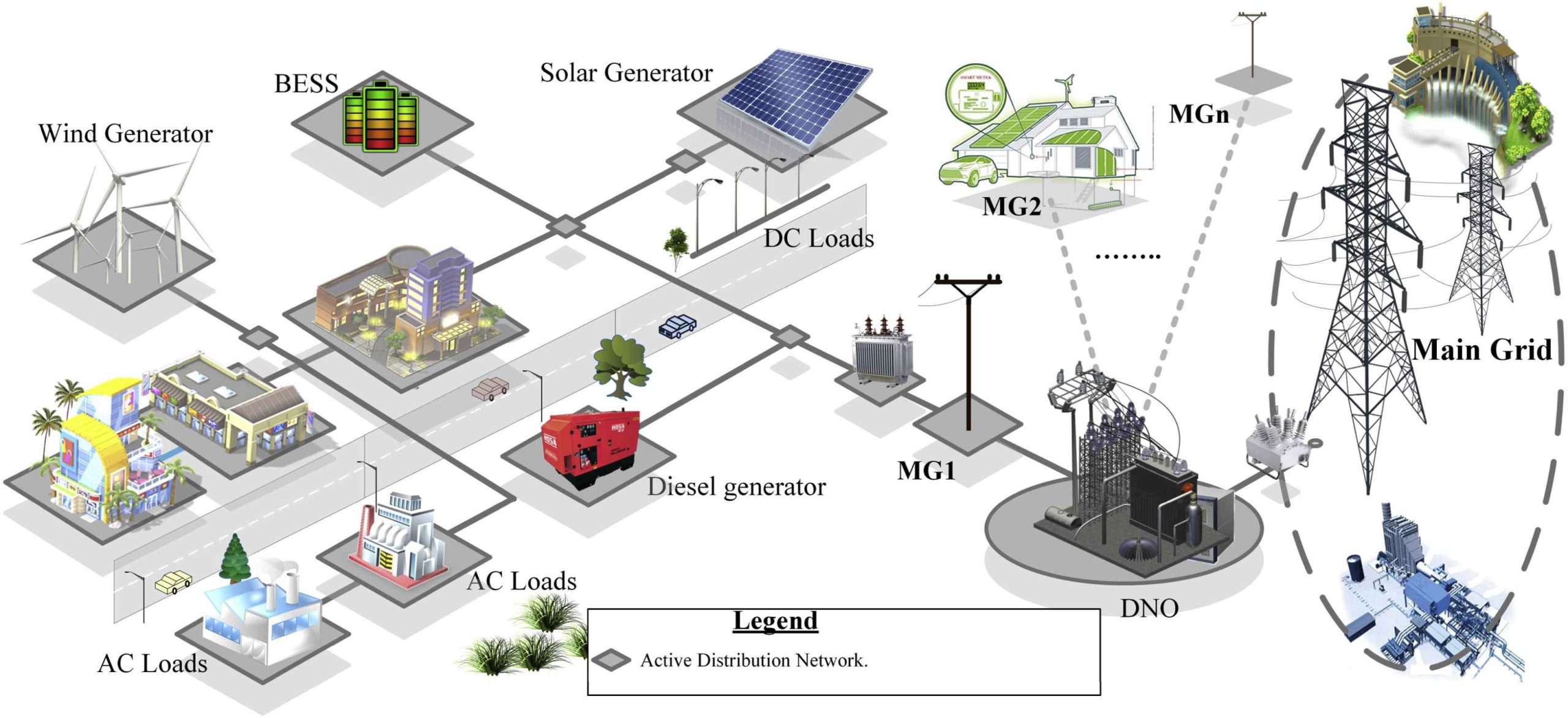

The core operational paradigm of an alternating current (AC) power grid is the instantaneous matching of real and reactive power supply with demand. The transmission network serves as the conduit for this energy transfer, yet a singular parameter does not define its capacity. Instead, the maximum permissible power flow on any given corridor is circumscribed by a hierarchy of physical laws and engineering design thresholds. These limitations—thermal, voltage, and stability—form the essential “power flow crux” that system planners and operators must navigate to ensure secure, stable, and economic grid operation.

2. The Tripartite Constraints on Power Transfer

2.1 Thermal Limitation: A Material Constraint

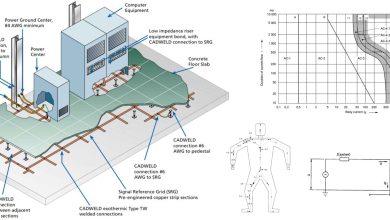

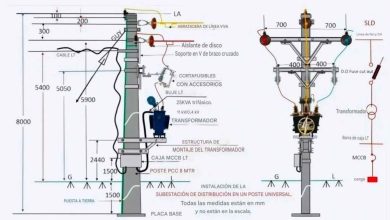

The most fundamental constraint arises from the physical properties of the conductor material. All current-carrying conductors possess a finite thermal rating, determined by the maximum current they can sustain without causing permanent damage or excessive sag. Exceeding this ampacity leads to Joule heating, conductor expansion, and a dangerous reduction in clearance to ground or adjacent objects. For shorter transmission segments (typically below 80 km), the power transfer capability is often directly limited by this thermal rating, as other constraints may not yet become dominant. This represents a hard material limit, primarily concerned with short-term equipment integrity.

2.2 Voltage Drop Limitation: A Service Quality Constraint

Over longer distances (generally exceeding 250-300 km), the series inductance and shunt capacitance of the line become significant. The flow of real and reactive power induces a voltage drop along the line, approximately proportional to the product of line impedance and power flow. Maintaining voltages within statutory limits (e.g., ±5% of nominal) at all connection points is critical for consumer equipment performance and system security. Consequently, on long lines, power flow must often be constrained below the thermal limit to prevent unacceptable voltage deviations at the receiving end, necessitating careful reactive power management and compensation.

2.3 Steady-State Stability Limitation: A Dynamic Synchronization Constraint

The most subtle yet critical constraint for long-distance AC power transfer is steady-state stability. The theoretical maximum transmissible power between two AC voltage sources (e.g., a generator and an infinite bus) separated by a reactance X is given by the well-known power-angle relationship:

P = ( Va x Vb x sinδ ) / X

Where (Va) and (Vb) are the voltage magnitudes, (X) is the connecting reactance, and (\delta) is the phase angle between the sources. While the equation suggests a maximum at (δ = 90°), practical systems operate with a much smaller security margin, typically maintaining (δ) between (30°) and (45°). This is because, as (δ) approaches (90°), the system becomes increasingly susceptible to losing synchronism following any small disturbance, such as a fault or load change. A loss of synchronism can lead to catastrophic generator trip-outs and cascading outages. Thus, stability imposes a restrictive ceiling on power transfer over long, inductive corridors—often the most stringent limit—which is frequently well below both the thermal and voltage-drop thresholds.

3. Synthesis and Interaction of Constraints

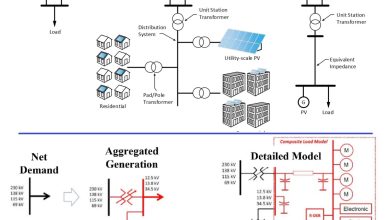

The dominance of each constraint is a function of line length and system strength. Short lines are thermally limited. As length increases, voltage regulation becomes paramount. For very long lines, steady-state stability invariably emerges as the governing constraint, preventing utilization of the conductor’s full thermal capacity. This hierarchy creates a significant gap between the theoretical thermal capability of transmission assets and their practical, stability-limited loading, representing a substantial under-utilization of infrastructure from a purely thermal perspective.

4. Modern Mitigations: Bridging the Gap Between Limits and Utilization

Contemporary power systems employ advanced technologies to alleviate classical constraints, effectively reshaping the power-flow envelope.

- Flexible AC Transmission Systems (FACTS): Devices such as Static Synchronous Compensators (STATCOMs) and Thyristor-Controlled Series Capacitors (TCSCs) provide fast, dynamic control of reactive power and line impedance. They enhance voltage profiles, dampen oscillations, and effectively increase the stability limit (by reducing the effective (X) in the power-angle equation), allowing power flows to move closer to thermal ratings.

- High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) Transmission: HVDC links decouple the connected AC networks, eliminating the stability limit imposed by the power-angle relationship. Power flow is electronically controlled and not limited by system synchronism, making HVDC ideal for very long-distance or asynchronous interconnections, allowing full exploitation of the conductor’s thermal capacity.

5. Conclusion: Toward a More Utilized and Reliable Grid

The operational limits of AC transmission networks are defined by a complex interaction of thermal, voltage, and stability constraints. Historically, the stability limit has been the most restrictive factor for long lines, leading to conservative operation and under-utilized assets. The integration of power electronics through FACTS and HVDC represents a paradigm shift, offering direct and dynamic control over the parameters that govern these limits. By enhancing controllability, these technologies are narrowing the gap between theoretical capability and practical operation. The future grid, underpinned by these advanced technologies, promises not only to operate closer to its physical limitations but to do so with greater robustness, reliability, and efficiency, fundamentally resolving the classic power flow crux that has long constrained system planners.