The Multidimensional Value Proposition of Distributed Energy Resources

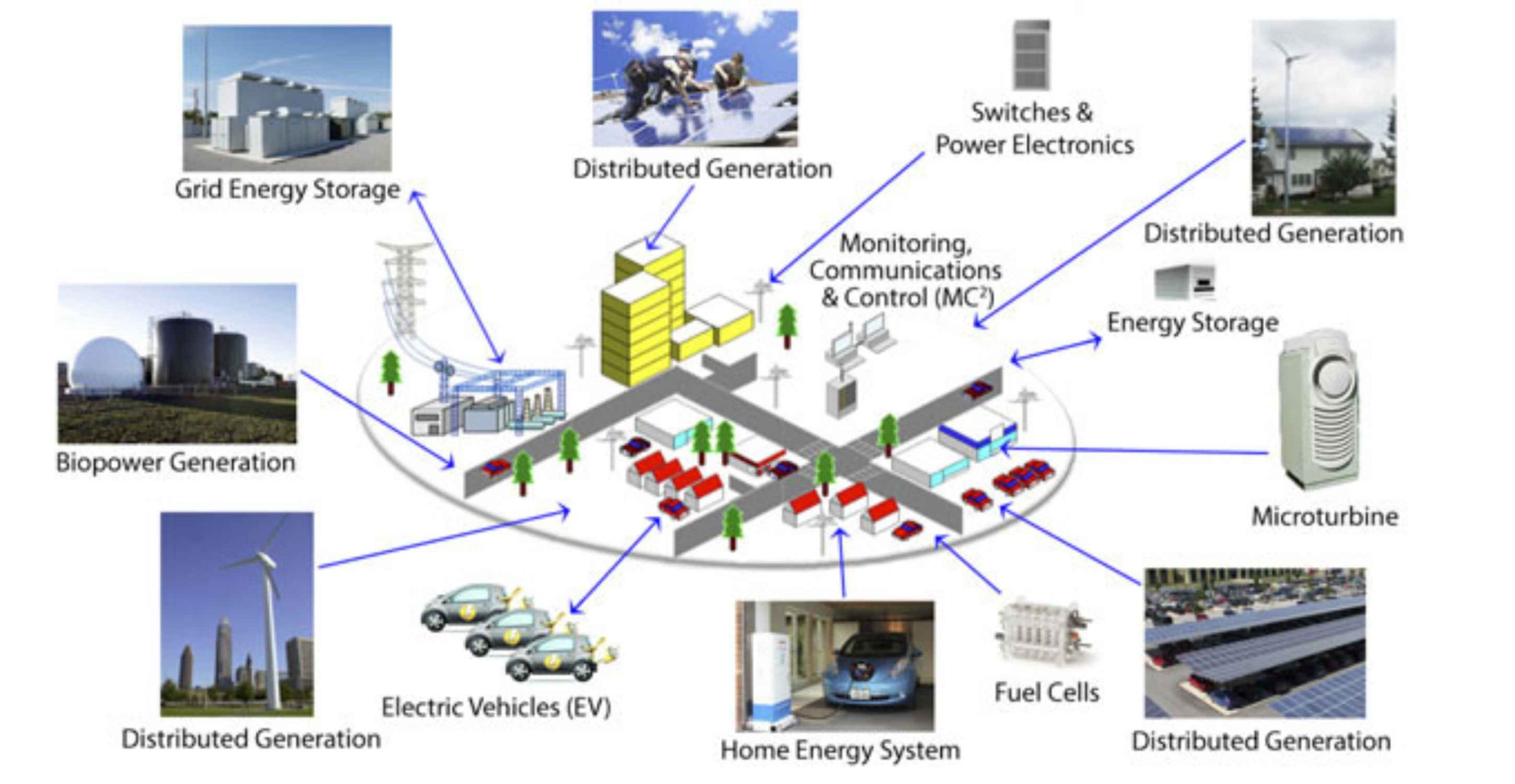

The provision of electric grid connectivity constitutes a valuable service by delivering requisite energy quantities at specific locations and times of need. This utility can be conceptualized as energy possessing volumetric, temporal, and locational value—a triad often overlooked in conventional discourse. A nuanced understanding of these value dimensions is critical for assessing the full potential of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs).

1. Volumetric Value

The volumetric value of energy is derived from the quantity supplied, a concept familiar through monthly billing based on kilowatt-hour (kWh) consumption. For instance, a consumption of 500 kWh in a given month corresponds directly to its volumetric value component. For DERs, this value equals the total energy output.

2. Capacity Value

Energy resources also provide capacity value, reflected in the fixed or demand charges of an electricity bill. These charges compensate for the guaranteed availability of a specified power capacity (e.g., 6 kW). In systemic terms, capacity value denotes a resource’s ability to deliver required power levels, forming the basis of capacity markets in certain regions. A DER possesses a capacity value if it can reliably meet peak demand, such as an energy storage system delivering 6 kW when needed.

3. Temporal Value

The value of energy fluctuates with time, increasing during periods of high demand—a principle analogous to dynamic pricing in transportation sectors. Time-of-use (TOU) tariffs operationalize this concept by applying premiums during peak hours and offering rebates during off-peak periods. For DERs, temporal value is maximized when generation coincides with peak demand, such as solar photovoltaic (PV) output aligning with daily load peaks.

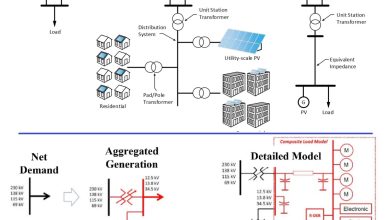

4. Locational Value

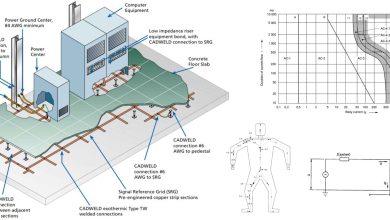

Locational value is paramount in unlocking DER benefits. Proximity to consumption points reduces transmission and distribution losses, enhancing economic and efficiency outcomes. For example, rooftop solar generation typically has greater locational value than remote utility-scale solar plants because of lower line losses and reduced grid congestion.

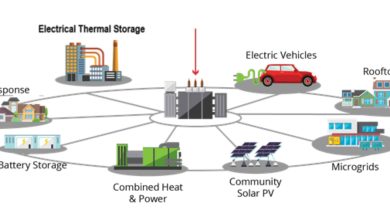

5. Additional Value Streams

Beyond these core dimensions, DERs can deliver supplementary value, including:

- Environmental Value: Avoided emissions from clean energy generation.

- Grid Capacity Value: Deferral or avoidance of distribution network upgrades through localized generation.

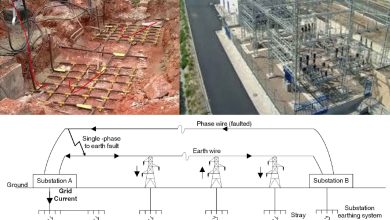

- Reliability and Resilience: DERs enhance system adequacy (sufficient supply) and security (fault tolerance), while resilience refers to maintaining operation during extreme events. For instance, during the 2018 Kerala floods, rooftop solar systems provided critical backup power.

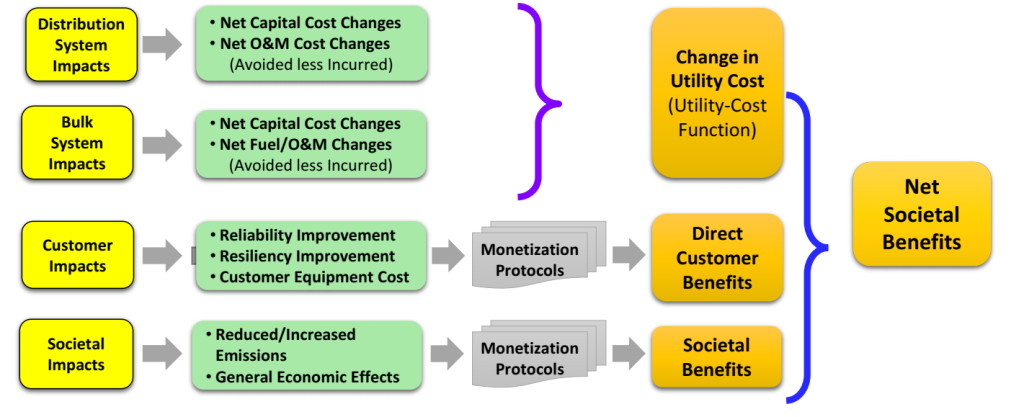

Valuation Methodologies

Frameworks such as the Electric Power Research Institute’s (EPRI) Cost-Benefit Analysis provide a structured approach to quantifying DER value, accounting for grid and societal impacts. Two principal valuation methods are:

- Value of Resource (VOR): Isolates and values utility service costs and DER benefits, incorporating both positive and negative externalities. Key value components include:

- Avoided energy/fuel costs

- Reduced line losses

- Avoided capacity investments

- Ancillary services

- Avoided pollution and CO₂ emissions

- Reliability enhancements

- Value of Service (VOS): Focuses on services rather than technologies, assessing how DERs can support distribution grid operations (e.g., voltage regulation, ramping, black-start capability).

Transactive Energy and Future Frameworks

Transactive Energy represents an emerging paradigm combining technical architecture with economic coordination, enabling DERs to respond dynamically to market signals. This approach facilitates peer-to-peer exchanges or utility contracts, broadening value realization beyond traditional grid services.

The Grid’s Value in a DER-Rich Future

The grid itself remains a critical asset, providing reliability during DER outages and enabling aggregation services that enhance overall system value. High DER penetration may encourage some consumers to operate independently, yet the grid’s role as a platform for integration and service exchange remains significant. Conversely, declining grid connectivity could diminish this collective value.

In summary, a comprehensive valuation of DERs must account for their multidimensional contributions—volumetric, temporal, locational, environmental, and systemic—while recognizing the evolving interplay between distributed resources and the centralized grid.