Importance of Transient Stability Studies in Modern Power Systems

Modern power systems operate in a highly dynamic environment where disturbances can occur at any moment. Among the most critical aspects of grid reliability is transient stability—the ability of the power system to remain in synchronism after a large, sudden disturbance over a short period.

Understanding and analyzing transient stability is essential for ensuring a safe, secure, and uninterrupted electricity supply.

What Are Electrical Transients?

A transient is a short-duration, high-frequency disturbance in voltage and current. These events typically last from a few milliseconds to several seconds and can significantly disturb generator rotor angles and speeds.

When a large disturbance occurs—such as a short circuit or sudden generator outage—the delicate balance between mechanical input power and electrical output power is disrupted. If the system cannot restore this balance quickly, parts of the grid may disconnect or, in severe cases, collapse entirely.

Transient stability differs from steady-state or small-signal stability because it addresses large disturbances over short time frames.

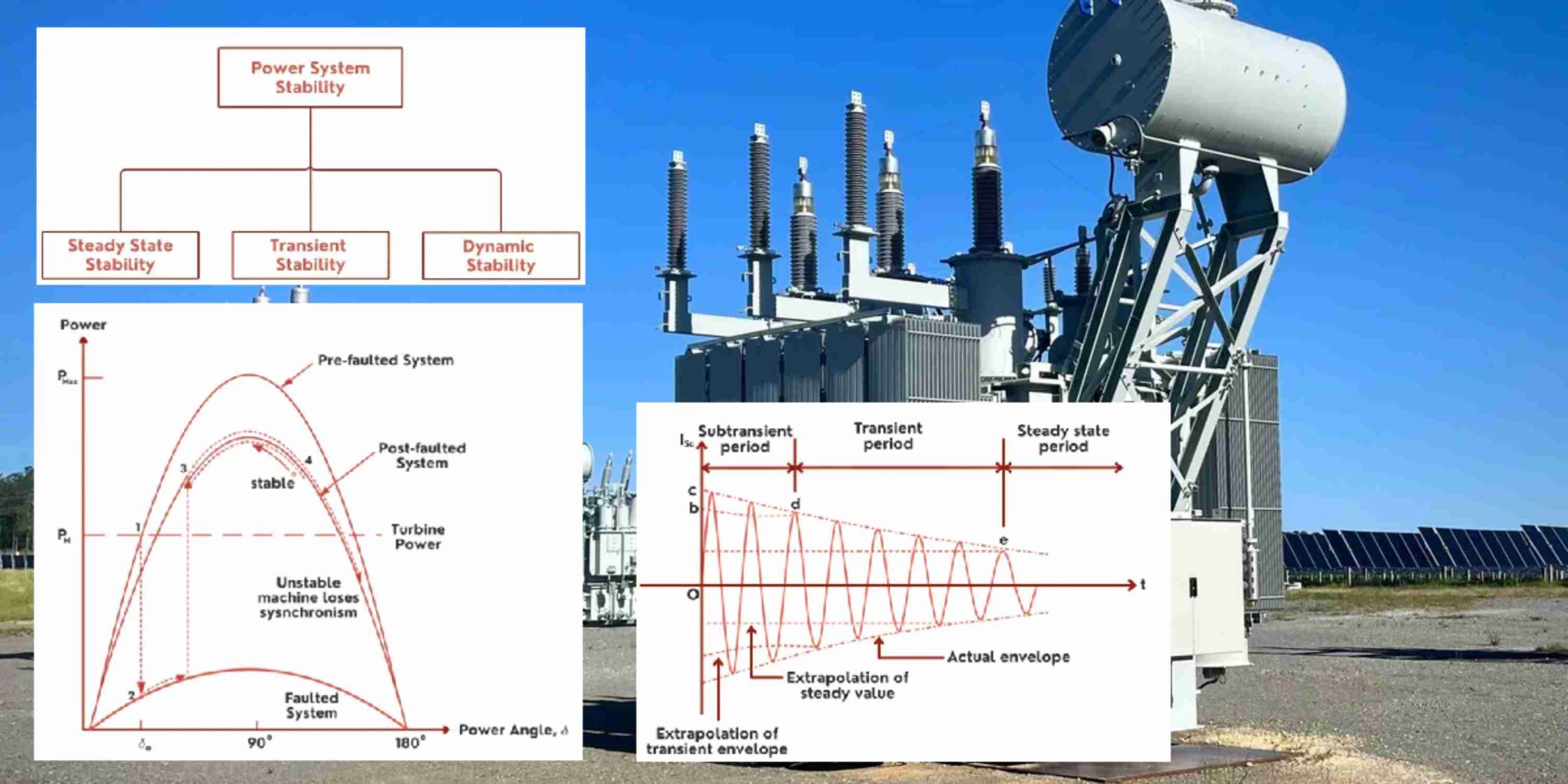

Power System Stability Classification

Power system stability is largely influenced by how synchronous machines respond dynamically to disturbances. Based on disturbance severity, stability is generally categorized into three main types:

1. Steady-State Stability

Steady-state stability refers to the system’s ability to maintain synchronism under small, gradual disturbances such as:

- Minor load changes

- Small adjustments in turbine input

- Voltage regulator setpoint variations

It defines the maximum power that can be transferred without losing synchronism under minor perturbations.

2. Transient Stability

Transient stability concerns the system’s response to large, sudden disturbances, including:

- Short circuits

- Sudden loss of generation

- Transmission line outages

Traditional transient stability studies focus primarily on:

- Network impedance

- Mechanical and electromagnetic characteristics of synchronous machines

Initial analyses often assume that excitation systems and prime movers respond more slowly than the disturbance duration, and their effects are neglected in early-stage evaluations.

Transient stability answers a critical question:

Can the system regain synchronism after a major fault is cleared?

3. Dynamic (Small-Signal) Stability

Dynamic stability evaluates the system’s ability to maintain synchronism under small but sustained disturbances over time.

Unlike traditional transient studies, dynamic stability includes:

- Automatic Voltage Regulators (AVRs)

- Turbine governors

- Power system stabilizers

It focuses on oscillation damping and on the behavior of the control system under continuous minor disturbances.

Why Transient Stability Analysis Is Important

Transient stability analysis plays a vital role in modern grid operation for several reasons:

Grid Reliability

Ensures the system can survive faults and continue operating without cascading failures.

Protection Coordination

Helps determine correct relay settings and breaker clearing times.

Planning and Expansion

Essential during:

- Grid expansion projects

- Generator additions

- Renewable energy integration

Regulatory Compliance

Required by standards such as:

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC)

- Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE)

- National Electrical Code (NEC)

Preventive Control

Identifies system weaknesses and supports proactive mitigation strategies.

As distributed energy resources (DERs), HVDC links, and market-based dispatch increase system complexity, transient stability studies have become even more critical.

Common Fault Types and Their Impact

Different faults affect system stability in different ways:

Three-Phase Fault

- Involves all three phases

- Most severe fault type

- Used for worst-case design scenarios

Line-to-Line Fault

- Occurs between two phases

- Causes waveform distortion and imbalance

Line-to-Ground Fault

- Most common in distribution systems

- Can escalate if grounding is inadequate

Bus Fault

- Affects multiple feeders and transformers

- Causes wide-area disruption

Generator Internal Fault

- Stator or rotor winding faults

- Causes immediate generator disconnection

Transformer or Load Switching Events

- Produce inrush currents and overvoltages

- Can destabilize weak systems

Fault duration is critical.

The longer a fault persists before clearing, the greater the rotor angle deviation—and the higher the risk of losing synchronism.

Fault location also matters: faults closer to generators tend to cause more severe instability.

Causes of Transient Instability

Beyond faults, instability can arise from:

- Delayed fault clearing

- Sudden generation loss

- Sudden load rejection

- Incorrect protection settings

- Heavily loaded transmission lines

- Insufficient system inertia (common in renewable-heavy grids)

- Breaker switching operations

In many historical blackouts, instability resulted from a combination of multiple factors rather than a single event.

The Mechanism Behind Transient Instability

At the heart of transient instability is rotor dynamics.

Under normal conditions:

- Mechanical power input equals electrical power output.

- Rotor speed remains constant.

- Machines operate in synchronism.

During a disturbance:

- Electrical power output suddenly drops (e.g., due to a fault).

- Mechanical input remains unchanged.

- The rotor accelerates.

If the rotor angle deviates too far from that of other generators, synchronism is lost. Once this happens, the generator must disconnect, potentially worsening the imbalance and triggering cascading outages.

Engineers often use the equal-area criterion to visually determine whether stability can be maintained. However, modern systems typically require detailed time-domain simulations due to complex controls and inverter-based resources.

Winding Response During a Transient

Different machine windings dominate at different stages:

Sub-Transient Period (Immediate Response)

- Damper windings react quickly.

- Oppose sudden current changes.

Transient Period

- Field winding manages slower flux changes.

Steady-State

- Armature (stator) winding governs normal power transfer.

Each stage operates on a different time scale, contributing to overall system stabilization.

Time Scales of Transient Events

Typical transient stability time frames include:

- 0–200 ms: Fault inception and relay action

- 200–500 ms: Breaker clearing and system response

- 0.5–5 seconds: Rotor oscillations and damping

Engineers analyze these using:

- Swing equation models

- One-machine infinite bus models

- Detailed machine models

- Network reduction techniques

- Real-time digital simulation

- Phasor Measurement Units (PMUs)

Outcomes of Transient Stability Studies

Proper transient stability analysis provides:

- Improved operational security

- Reduced blackout risk

- Equipment protection

- Better protection coordination

- Renewable integration validation

- Design verification before implementation

In modern electrified grids, stability studies do more than prevent failure—they enable innovation. Large-scale solar and wind plants, for example, must meet fault-ride-through and dynamic performance requirements before receiving grid connection approval.

Mitigation Strategies

To enhance transient stability, engineers implement:

Fast Fault Clearing

Upgrading relays and breakers to minimize clearing time.

Power System Stabilizers (PSS)

Add damping to rotor oscillations.

FACTS Devices

- STATCOM

- SVC

- TCSC

Regulate voltage and power flow dynamically.

Inertia Support

- Synchronous condensers

- Synthetic inertia from inverters

Remedial Action Schemes (RAS)

Automated load shedding or generation tripping.

Generator Control Optimization

Fine-tuning governors and exciters.

Additional Measures

- Grid reinforcement

- Controlled islanding

- Adaptive protection systems

Effective mitigation requires system-specific analysis and a layered engineering approach.

Conclusion

Transient stability studies are fundamental to modern power system reliability. They allow engineers to predict how the grid will respond to sudden disturbances and ensure it can recover without losing synchronism.

As electrical grids become more complex—with higher renewable penetration, advanced controls, and interconnected markets—transient stability analysis is no longer optional. It is a cornerstone of secure planning, operational excellence, and resilient infrastructure.

In short, transient stability is not just about preventing blackouts—it is about enabling the future of power systems safely and confidently.