District Energy Systems: Principles, Efficiency, and Modern Applications

Executive Summary

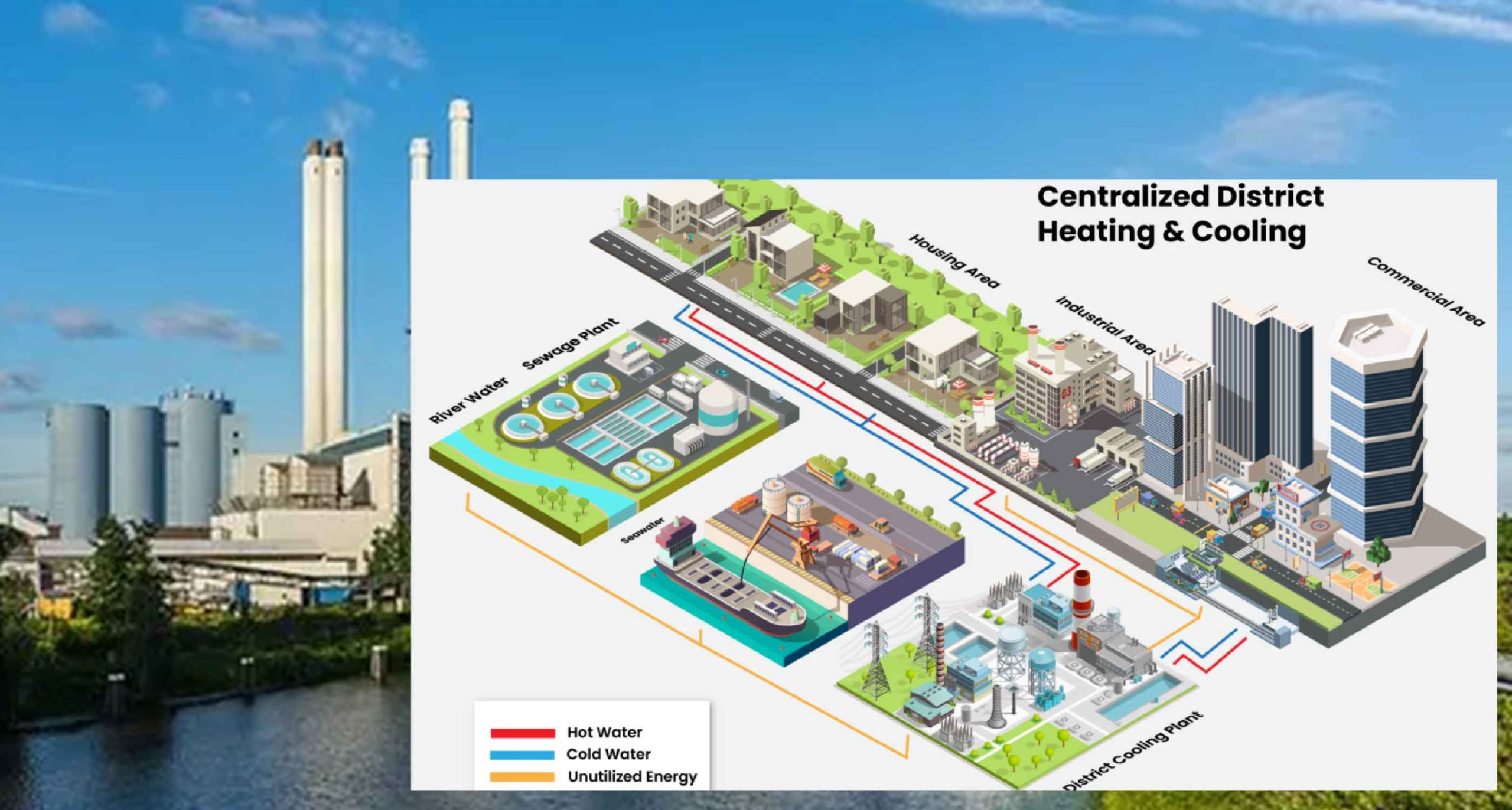

District energy systems represent a centralized approach to the generation and distribution of thermal and electrical energy. By consolidating the heating, cooling, and power requirements of multiple buildings into a single, high-efficiency plant, these systems offer significant economic and environmental advantages over decentralized alternatives. Commonly deployed in dense urban environments, universities, hospitals, and military installations, district energy provides a robust framework for enhancing energy security, improving resource efficiency, and integrating diverse energy sources into a cohesive local grid.

1. Conceptual Overview of District Energy

At its core, a district energy system consists of a central plant that produces steam, hot water, or chilled water, which is then distributed through a network of insulated underground pipes to provide space heating, domestic hot water, and air conditioning to a cluster of buildings. This centralized model eliminates the need for individual boilers, furnaces, or chillers in every building, thereby optimizing space and reducing maintenance overhead.

1.1. Historical Context

The precedent for modern district energy was established by Thomas Edison in 1884 with the Pearl Street Station in Manhattan. This facility utilized reciprocating steam engines to generate electricity, while simultaneously capturing exhaust steam to heat nearby buildings. This early application of Combined Heat and Power (CHP) laid the foundation for the sophisticated multi-service plants in operation today.

2. Operational Mechanics and Efficiency

District energy plants are engineered to maximize the thermal potential of fuel sources. While traditional decentralized systems suffer from cumulative losses across numerous small-scale units, centralized plants leverage economies of scale and advanced technology to maintain superior performance.

2.1. Thermal Efficiency and System Losses

The efficiency of a modern fossil-fueled boiler typically ranges between 85% and 90%. In a district heating context, approximately 10% of thermal energy is lost during distribution through the piping network. This results in an overall system efficiency of 75% to 80%. While a 20% to 25% total energy loss may seem significant, it is substantially lower than the aggregate losses incurred if each building operated its own independent heating and cooling infrastructure.

2.2. Diversified Service Offerings

Modern district energy plants often function as multi-utility hubs, providing a suite of essential services beyond simple heating:

- Thermal Energy: High-pressure steam for heating and industrial processes.

- Cooling: Chilled water for large-scale air conditioning systems.

- Electricity: On-site power generation, often through cogeneration.

- Ancillary Services: Purified water, compressed air, and specialized cooking steam.

3. District Cooling Systems (DCS)

A critical subset of district energy is the District Cooling System (DCS). This centralized network provides chilled water to multiple buildings for air conditioning and industrial cooling.

3.1. Core Components of DCS

A functional district cooling system comprises three primary elements:

- Central Chiller Plant: Generates chilled water using high-efficiency industrial chillers.

- Distribution Network: A network of insulated underground pipes that circulates the chilled water.

- User Stations: Heat exchangers within individual buildings that transfer the “coolness” from the district network to the building’s internal HVAC system.

3.2. Strategic Benefits of District Cooling

The adoption of DCS offers several transformative advantages for urban environments:

- Energy Efficiency: Centralized plants are significantly more efficient than individual rooftop units, reducing aggregate energy consumption.

- Environmental Sustainability: Lower energy demand translates to reduced greenhouse gas emissions, aligning with global climate goals.

- Space Optimization: Eliminating individual chillers and cooling towers frees up valuable real estate for green spaces or additional commercial use.

- Reliability and Scalability: Redundant systems ensure uninterrupted service for critical facilities like data centers, while the network can be expanded to meet growing urban demands.

3.3. Implementation Challenges

Despite its benefits, DCS implementation faces specific hurdles:

- High Capital Expenditure: The initial investment for central plants and underground piping is substantial.

- Infrastructure Complexity: Planning and maintaining extensive subterranean networks require significant coordination among stakeholders.

- Resource Dependency: These systems often rely on water for cooling, necessitating robust water management strategies in arid regions.

4. Strategic Advantages: Redundancy and Reliability

One of the primary drivers for district energy adoption is the inherent redundancy and reliability it provides to critical infrastructure.

4.1. Infrastructure Redundancy

Unlike conventional power plants that may rely on a single generation unit, district energy plants typically employ a diverse array of equipment, including multi-fuel boilers, combustion turbines, and Heat Recovery Steam Generators (HRSGs). This ensures service continuity even during equipment failure or fuel supply disruptions.

4.2. Integration with Microgrids

As the global energy landscape transitions toward variable renewable sources, district energy plants are increasingly being integrated into microgrids. By combining the flexibility of centralized thermal storage with the stability of on-site generation, these systems can balance the intermittency of renewables.

5. Global Adoption and Case Studies

Cities worldwide are increasingly adopting district energy as a cornerstone of sustainable development.

- Stockholm, Sweden: Operates one of the world’s most extensive district heating and cooling networks.

- Singapore: Utilizes large-scale district cooling to manage high cooling loads in a tropical urban environment.

- Dubai, UAE: Employs massive DCS networks to provide efficient cooling in extreme desert climates.

6. Conclusion

District energy and cooling systems represent a paradigm shift in urban infrastructure. By leveraging centralized networks, cities can mitigate the environmental impact of energy demands while ensuring comfort, reliability, and economic viability. As climate challenges intensify, investing in these innovative, holistic solutions becomes a necessity for a sustainable future.