On the Conceptual Distinction Between Distributed Energy Resources (DER) and Distributed Renewable Energy (DRE)

1. Introduction

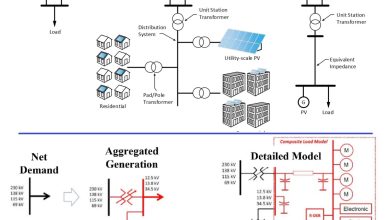

In the context of technological disruption within the energy sector, terminology can often create conceptual ambiguity. A notable example is the distinction between the acronyms DER (Distributed Energy Resources) and DRE (Distributed Renewable Energy). While superficially similar, these terms represent meaningfully different concepts. DRE refers specifically to renewable energy generation—such as solar, wind, or biomass—that is interconnected to the electrical distribution network, which typically operates at voltages up to 69 kV and supplies end-use consumers. DER, however, constitutes a broader and more complex category of grid-connected resources.

2. Defining “Distributed” and “Decentralized.”

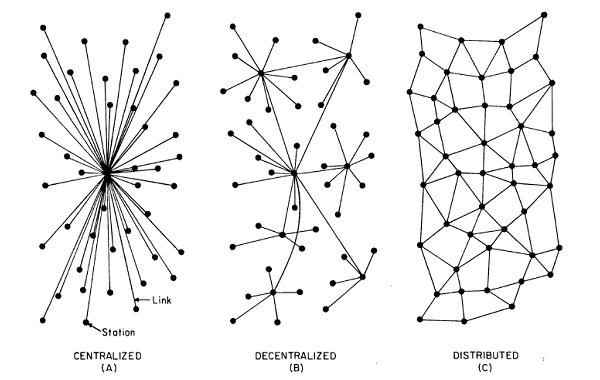

Before examining DER in detail, it is essential to clarify the term “distributed.” Within energy systems discourse, “distributed” and “decentralized” are frequently used interchangeably, though they are not synonymous. Drawing from network theory, a decentralized system is characterized by the elimination of a single central control node, enabling control across multiple nodes. Such systems are often associated with off-grid configurations, but are not exclusively so.

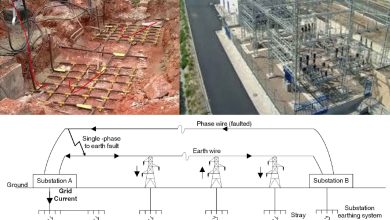

Structurally, decentralization can be understood as a subset of distributed networks. In electrical systems, the distribution network—generally operating at 69 kV or below—constitutes the physical infrastructure to which distributed resources are connected.

3. Conceptualizing Distributed Energy Resources (DER)

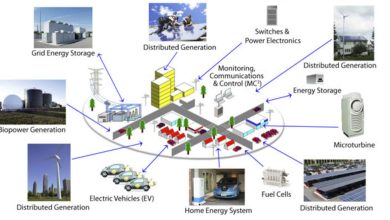

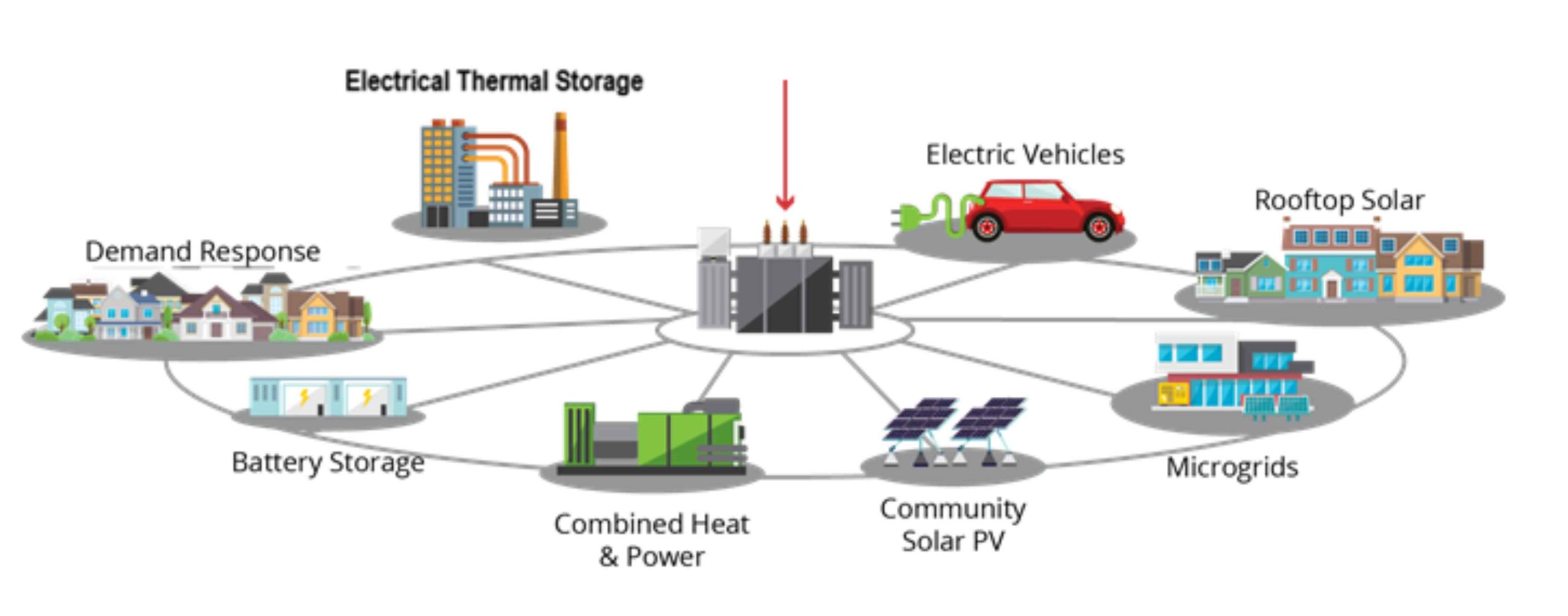

A Distributed Energy Resource is defined, in part, by its point of interconnection: it must be connected to the distribution network. The complexity arises in defining what constitutes an “energy resource.” Beyond conventional distributed generation (e.g., solar PV), the category may include:

- Energy storage systems (e.g., batteries, thermal storage)

- Electric vehicles (when providing grid services)

- Demand response mechanisms

- Energy efficiency measures

- Microgrids and energy management systems

Seminal work by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) in its Future of Electric Utility Regulation series helped establish this inclusive scope, incorporating clean and renewable distributed generation, storage, demand response, and efficiency. This framing has been adopted by several U.S. regulatory bodies, including the California Public Utilities Commission and the New York Public Service Commission, and Massachusetts has further extended it to include microgrids and energy management systems. Notably, DER encompasses only clean or renewable generation; systems reliant on diesel generators, for instance, are excluded. Consequently, DRE is correctly understood as a subset of DER.

One widely referenced definition, formulated by the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), specifies that DER must satisfy the first criterion below, plus at least one of the subsequent three:

- Interconnection: Approved grid connection at or below 69 kV.

- Generation: Electricity production from any primary fuel source.

- Storage: Energy storage capable of supplying electricity to the grid.

- Demand-Side Management: Load modifications by end-use customers in response to price signals or other incentives.

4. Relevance of DER for India

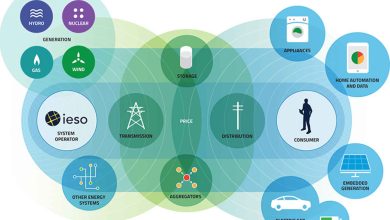

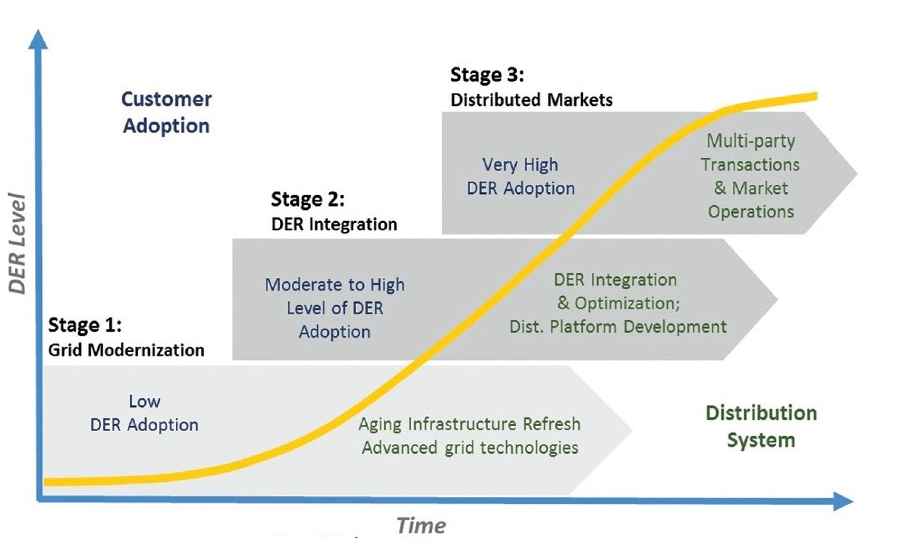

Although DER, as a regulatory construct, has been primarily developed in the United States, its underlying technological and systemic drivers are global. In India, as elsewhere, the traditional centralized model of generation, transmission, and distribution is being transformed by the emergence of prosumers and distributed storage. Increasing DER penetration presents both operational challenges for utilities and opportunities for deferred infrastructure investment. For consumers, DER can yield savings in energy and demand charges.

For Indian regulators, DER offers a unifying framework to evaluate diverse resources located near consumption points. This includes not only DRE from solar, wind, and biomass, but also distributed storage, electric vehicles, and energy efficiency. A holistic regulatory approach to DER can streamline tariff determination, cost-benefit analysis, and the design of compensation mechanisms—for instance, for electric vehicle charging.

5. Conclusion

This discussion provides only an introductory overview of the possibilities and regulatory challenges associated with DER. Its continued expansion appears inevitable, potentially leading toward transactive energy markets and peer-to-peer energy exchanges. A shift from a cost-of-service to a value-of-service regulatory paradigm may become imperative. Subsequent analysis will address valuation methodologies and the evolution of transactive energy frameworks.