The Evolving Definition and Implications of Distributed Energy Resources

The axiom that “change is the only constant” is particularly apt in the energy sector, where technological and conceptual shifts continuously reshape foundational definitions. The concept of Distributed Energy Resources (DER) exemplifies this evolution, as its scope and characterization have transformed significantly over time.

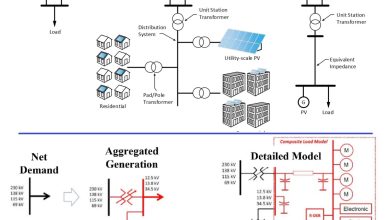

Historically, DER was defined primarily in terms of localized generation technologies. For instance, a seminal 2008 review characterized DER as encompassing technologies such as diesel engines, microturbines, fuel cells, photovoltaics, and small wind turbines. A decade later, the definition had expanded considerably. By 2018, DER was conceptualized not only as customer-sited supply but also as a grid resource capable of reducing demand or providing various grid services. This broader definition explicitly includes energy efficiency (EE) and demand response (DR), alongside solar PV, wind, combined heat and power, energy storage, electric vehicles, and microgrids.

This expansion, however, is not without contention. A central question in the discourse is whether EE and DR legitimately constitute DER. Proponents argue that EE provides verifiable energy and demand savings, displacing fossil-fuel generation, while DR serves as a flexible resource for balancing supply and demand [2]. Reflecting this view, the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC) classifies both as DER. Conversely, technical standards such as IEEE 1547, which governs interconnection, explicitly exclude DR and other loads, focusing instead on distributed generation sources. This discrepancy highlights a fundamental tension between a broad, functional perspective and a narrower, technology-specific one.

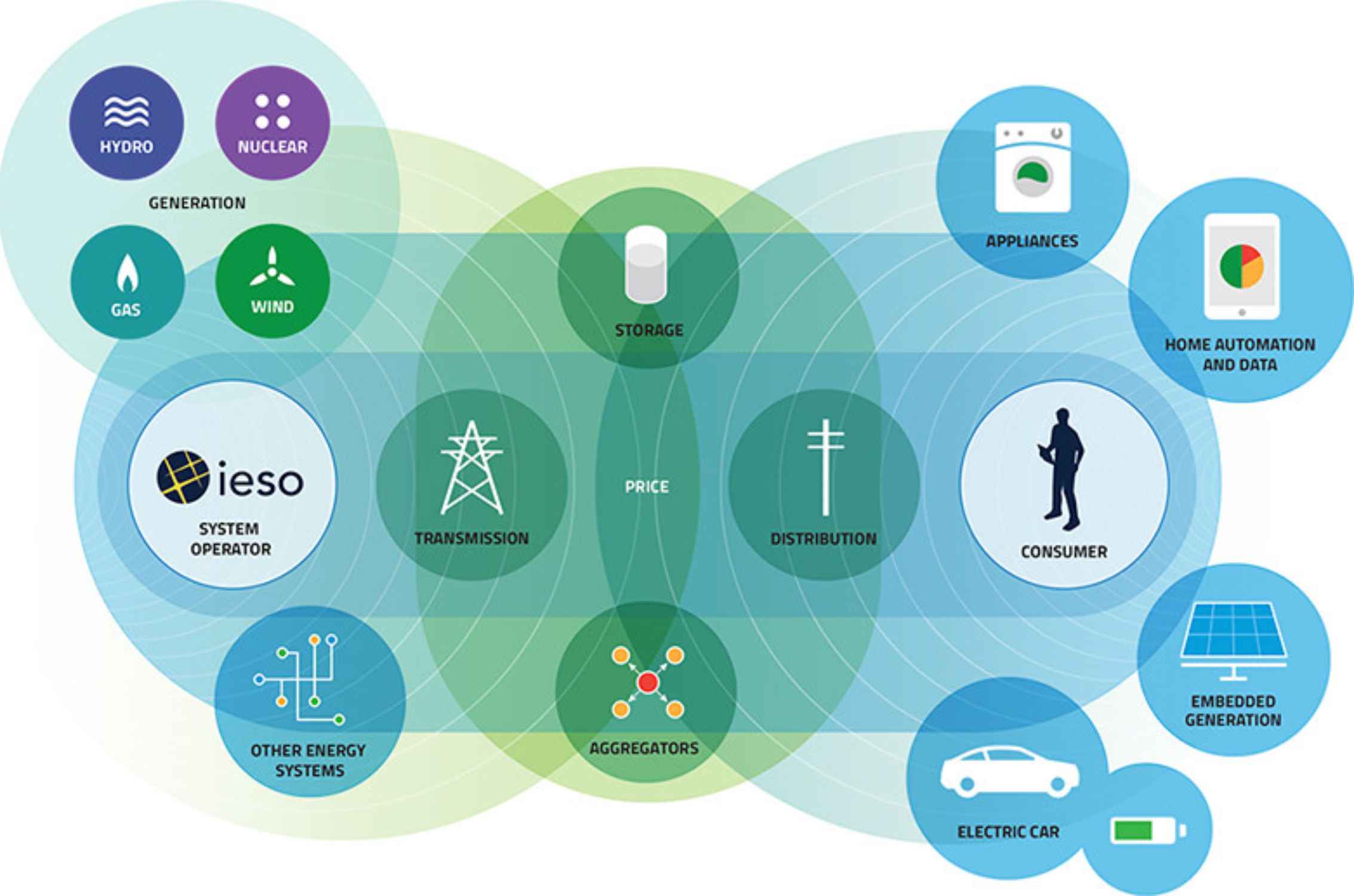

The conceptualization of DER also varies internationally, though a prosumer-centric and increasingly “green” orientation is common. In Canada, the Independent Electricity System Operator defines DER to include clean energy resources within the distribution system, encompassing solar, CHP, storage, small natural gas generators, electric vehicles, and controllable loads. Similarly, in Australia, while official definitions permit both renewable and non-renewable behind-the-meter generation, cited examples predominantly emphasize clean technologies like rooftop solar, wind, storage, and EVs. The European perspective often simplifies DER into a triad of on-site generation, storage, and demand-response resources, with collaborative efforts underway to standardize grid integration protocols.

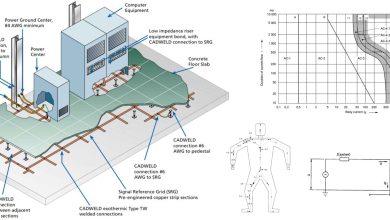

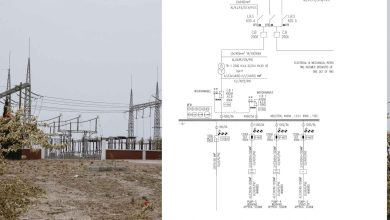

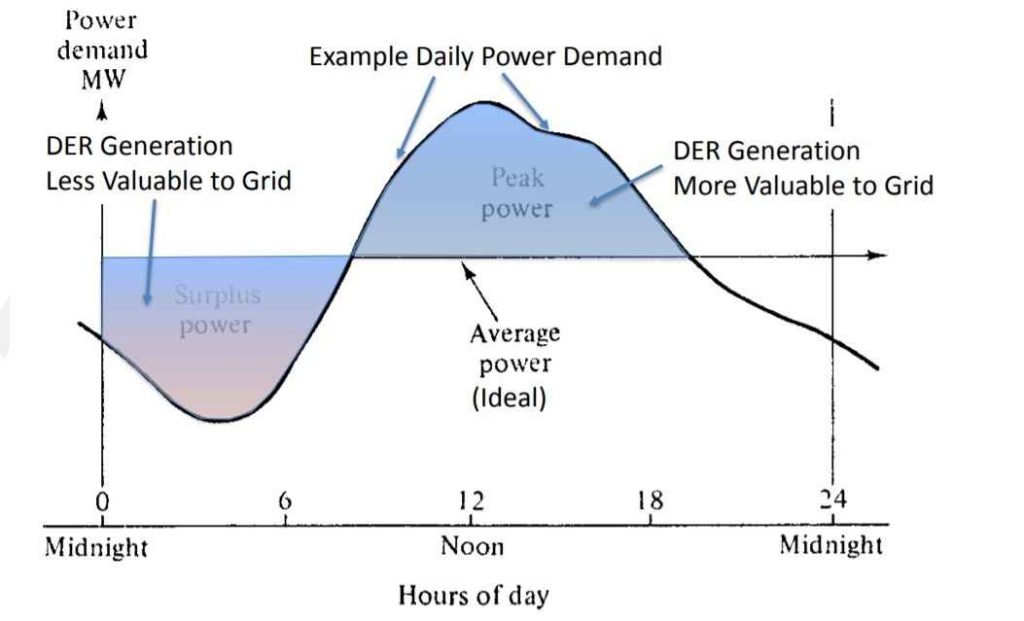

The value and impact of DER on the grid are contingent on context and implementation. DER can provide substantial benefits, including deferring distribution network upgrades, reducing line losses, lowering emissions, providing backup power, reducing demand charges, enabling energy arbitrage, and providing voltage, frequency, and black-start support. Its value is often highest during peak periods when it can alleviate network constraints.

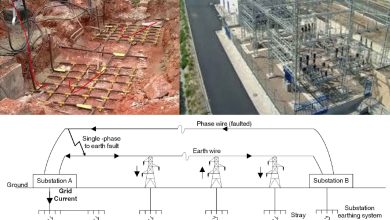

Nevertheless, high DER penetration levels introduce significant technical and planning challenges. DER technologies exhibit diverse characteristics; some, such as storage, are dispatchable, while others, such as solar and wind, are variable and intermittent. This variability necessitates careful system integration. A key concept in this regard is “hosting capacity”—the maximum DER a circuit can accommodate without infrastructure upgrades, determined by thermal limits and system design. Exceeding this capacity can threaten distribution network reliability and alter power flows, thereby impacting bulk power system dynamics. Consequently, accurate modeling and representation of DER have become critical for effective grid planning and operation.

In conclusion, DER represents a dynamic and expanding domain within the energy landscape. Its definition has evolved from a focus on distributed generation to a more holistic model incorporating demand-side resources. While offering considerable benefits for grid modernization and decarbonization, its integration requires careful management of its diverse characteristics and impacts on system reliability and planning.