Hydropower: The Evolution and Mechanics of Water-Driven Energy

Executive Summary

Water is among the most formidable and essential resources on Earth, possessing the dual capacity to sustain biological life and exert immense physical force. From the rudimentary irrigation canals of ancient Mesopotamia to the massive impoundment facilities of the modern era, humanity has sought to harness the kinetic and potential energy of water. This document, the first in a series on hydropower, examines the historical progression of water-driven technology, the fundamental physics of fluid dynamics, and the engineering considerations required to transform hydraulic energy into utility-scale electricity.

1. Historical Context: From Irrigation to Industrialization

The utilization of water for mechanical work dates back millennia. While early hydraulic engineering focused on water management for agriculture, the invention of the water wheel—credited to Greek engineers as early as 4000 BCE—marked a pivotal shift. Initially used for water lifting, the technology was eventually reversed to drive machinery, catalyzing an industrial boom.

1.1. The Evolution of the Water Wheel

For centuries, engineers refined the water wheel to power grain mills, lumber yards, and mining operations. Two primary designs emerged during the Industrial Revolution:

- Undershot Water Wheels: Designed to capture the kinetic energy of natural river flow.

- Overshot Water Wheels: Engineered to convert potential energy by utilizing the “head” (height) of falling water.

1.2. The Transition to Hydro-Electric Power

The 1880s introduced the “Age of Electricity,” where water wheels were adapted to drive dynamos. This evolution led to the development of the hydroelectric turbine, transforming hydropower into a primary utility-scale energy source. Iconic structures like the Hoover Dam (2,079 MW) exemplify this era, creating vast reservoirs such as Lake Mead to provide consistent power and water regulation.

2. The Physics of Hydropower

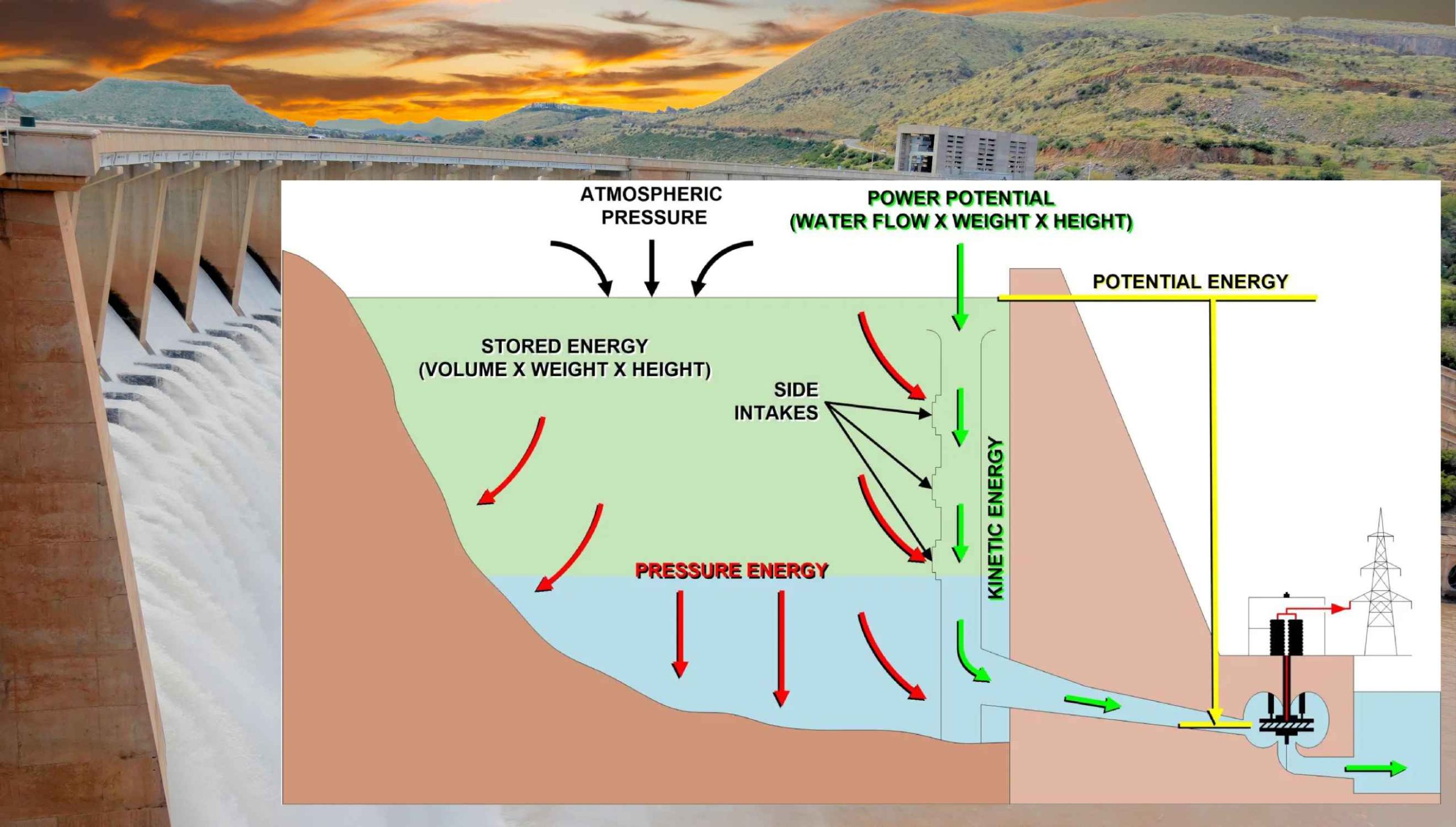

While the concept of capturing energy from flowing water is simple in principle, its application involves complex fluid dynamics. The energy available in a hydropower system is governed by Bernoulli’s Equation, which relates three primary forms of energy:

| The energy inherent in water is due to the pressure exerted upon it. | Description |

| Pressure Energy | The energy inherent in water due to the pressure exerted upon it. |

| Potential Energy | The energy derived from the elevation or “head” of the water source. |

| Kinetic Energy | The energy resulting from the velocity of the water flow. |

2.1. Turbine Selection and Efficiency

Turbine designs are tailored to the available energy profile of a site. Applications are generally categorized into low-head and high-head systems:

- High-Head Systems: Utilize significant elevation changes to drive turbines at high velocities.

- Low-Head Systems: Often rely on large flow rates rather than extreme pressure.

2.2. Stored Capacity and “Live Storage.”

The volume of water available at a required head is often compared to a battery, known as stored capacity or live storage. A decline in reservoir levels—as seen at the Hoover Dam in 2022—directly reduces the rated output of the turbines, as the available energy is insufficient for full-power operation.

3. Engineering and Site Selection

The design of a hydropower plant requires a rigorous analysis of energy availability, cost-efficiency, and environmental impact.

3.1. Run-of-River Facilities

Run-of-river designs utilize the river’s natural flow and elevation with minimal landscape modification. Water is typically diverted through a penstock to a powerhouse or passed through a diversion adjacent to the turbines. These facilities are ideal for rivers with consistent, high-energy flows.

3.2. Impoundment and Storage Facilities

When natural flow is inconsistent or insufficient, impoundment facilities (dams) are constructed to create reservoirs. These systems offer several advantages:

- Reliability: They provide a consistent water supply, mitigating the effects of seasonal droughts or floods.

- Grid Stability: They serve as a rapid-response energy source to balance the variability of other renewables, such as wind and solar.

- Multipurpose Use: Reservoirs often support municipal water needs, agriculture, and recreation.

4. Environmental and Social Considerations

The scale of modern hydropower projects necessitates careful consideration of their broader impacts. Large-scale impoundments can lead to significant habitat displacement. For instance, the Three Gorges Dam in China (22,500 MW) created a 419-square-mile reservoir, necessitating the relocation of 1.3 million people. The sheer mass of water stored in such reservoirs is so substantial that it can exert measurable effects on geophysical properties, such as the Earth’s rotation.

5. Conclusion

Hydropower remains a cornerstone of the global renewable energy portfolio. By bridging the gap between ancient mechanical principles and modern fluid dynamics, it provides a scalable, reliable, and flexible solution for the world’s growing energy demands. As we continue to integrate variable energy sources into the grid, the role of hydropower—particularly its storage and regulation capabilities—will be more critical than ever.