Enhancing Grid Resilience: Strategies for a Modern Energy Landscape

Executive Summary

In an era characterized by accelerating climate change, the retirement of conventional fossil-fuel assets, and the rapid integration of intermittent renewable energy sources, the stability of the electrical grid has become a paramount concern. The transition from a centralized, predictable model to a dynamic, decentralized system necessitates a shift in focus from mere reliability to comprehensive grid resilience. This document explores the multi-faceted nature of grid resilience, the pressures facing contemporary power systems, and the strategic interventions required to ensure a robust and adaptable energy infrastructure.

1. Defining Grid Resilience

Grid resilience is defined as the capacity of a power system to withstand, adapt to, and rapidly recover from disruptive events. Unlike traditional reliability metrics, which focus on the frequency and duration of outages under normal operating conditions, resilience addresses high-impact, low-probability events. These disruptions may be categorized into two primary types:

- Natural Hazards: Hurricanes, wildfires, ice storms, and extreme temperature fluctuations.

- Human-Induced Threats: Cyberattacks, physical sabotage, operational errors, and equipment failures.

A resilient grid is characterized by its redundancy (alternative pathways and backup systems), flexibility (the ability to reroute power and integrate diverse sources), and proactive intelligence (real-time monitoring and predictive analytics).

2. Drivers of Grid Vulnerability

The modern power grid faces unprecedented pressures that expose vulnerabilities in legacy infrastructure. Key drivers include:

- Anthropogenic Climate Change: Increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events challenge the physical limits of existing assets.

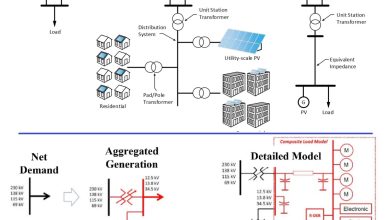

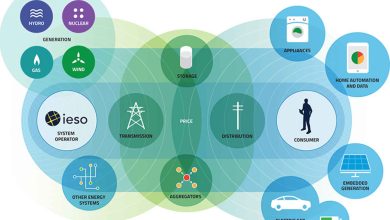

- Decentralization of Energy Resources: The proliferation of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs), such as rooftop solar and electric vehicles (EVs), introduces bidirectional power flows and increased variability.

- Cybersecurity Risks: As the grid becomes increasingly digitized, the attack surface for sophisticated cyber-threats expands, targeting control systems and data integrity.

- Electrification and Load Growth: The expansion of data centers and EV charging infrastructure pushes peak loads to new heights, straining capacity.

- Infrastructure Obsolescence: Aging components in many regions are ill-equipped to handle the dynamic requirements of a 21st-century energy system.

3. Strategic Pillars of Grid Resilience

To address these challenges, a multi-layered approach to resilience is essential. The following six pillars represent the core strategies for modernizing the grid.

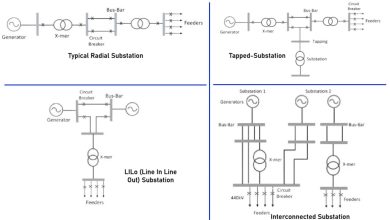

3.1. Grid Hardening: Physical Infrastructure Fortification

Grid hardening involves physical enhancements to make infrastructure more durable. Key measures include:

- Undergrounding: Relocating distribution lines underground in high-risk zones (e.g., hurricane-prone or wildfire-sensitive areas).

- Vegetation Management: Systematic clearing of rights-of-way to prevent contact between flora and energized lines.

- Structural Reinforcement: Utilizing composite or steel poles and advanced guy-wire configurations to withstand high winds and seismic activity.

- Asset Protection: Elevating substations above flood levels and applying fire-resistant coatings to critical components.

3.2. Energy Storage: The Nexus of Flexibility

Energy storage systems, including Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) and pumped hydro, serve as a critical buffer. They enable:

- Time-Shifting: Storing excess renewable generation for use during peak demand or low-production periods.

- Frequency Regulation: Providing near-instantaneous response to maintain system stability.

- Islanding Support: Facilitating the independent operation of microgrids during broader system failures.

3.3. Advanced Grid Monitoring and Intelligence

The transition from reactive to proactive management is driven by real-time data.

- Phasor Measurement Units (PMUs): Provide high-fidelity, time-stamped data to detect instabilities before they cascade into blackouts.

- Smart Metering Infrastructure (AMI): Enables precise outage detection and supports dynamic pricing models.

- AI and Predictive Analytics: Machine learning algorithms forecast equipment failure and identify anomalies indicative of cyber-intrusions.

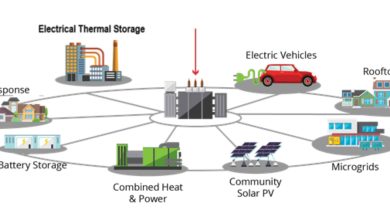

3.4. Microgrids and Distributed Energy Resources (DERs)

Microgrids provide localized resilience by allowing specific clusters—such as hospitals or military bases—to operate in “island mode.” DERs, including small-scale solar and V2G (Vehicle-to-Grid) technology, decentralize generation, reducing the impact of single-point failures in the centralized system.

3.5. Demand Response (DR): Consumer-Centric Stability

Demand response transforms consumers from passive users into active grid participants. By incentivizing load reduction or shifting during peak periods, DR reduces the need for expensive, carbon-intensive “peaker” plants, thereby easing system stress and preventing rolling blackouts.

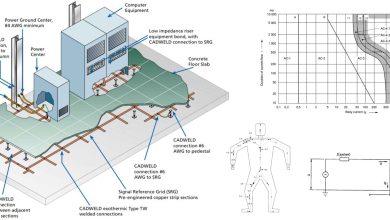

3.6. Cybersecurity: Defending the Digital Frontier

As a complex cyber-physical system, the grid requires robust digital defenses. This includes:

- Network Segmentation: Isolating operational technology (OT) from information technology (IT) networks.

- Encryption and Authentication: Securing communication between smart devices and control centers.

- Continuous Monitoring: Implementing real-time threat detection to identify and neutralize malicious activity.

4. Comparative Analysis of Resilience Strategies

The following table summarizes the primary functions and benefits of the key resilience strategies discussed.

| Strategy | Primary Focus | Key Benefit | Implementation Example |

| Grid Hardening | Physical Durability | Reduced storm damage | Undergrounding power lines |

| Energy Storage | Flexibility & Balancing | Smoothing intermittency | Large-scale BESS installations |

| Advanced Monitoring | Situational Awareness | Proactive fault detection | Deployment of PMUs |

| Microgrids/DERs | Localized Autonomy | Continuity for critical loads | Hospital-based solar + storage |

| Demand Response | Load Management | Peak demand reduction | Smart thermostat programs |

| Cybersecurity | Data & Control Integrity | Protection against sabotage | OT network segmentation |

5. Conclusion: A Resilient Path Forward

Grid resilience is no longer an optional enhancement; it is a fundamental requirement for national security, economic stability, and public safety. As the global energy landscape shifts toward a clean, electrified, and decentralized future, resilience must be “baked into” every level of system design. While it is impossible to eliminate every threat, integrating physical hardening, digital intelligence, and flexible resources ensures the modern grid can withstand the pressures of a changing world without breaking.